I listened to “He’s Gone” in the sweltering summer heat, as the presidential campaign season dragged on, and thought to myself, This thing is going to be so satisfying to play loud on the day after Donald Trump loses the election. Through it all, I kept a special place for “He’s Gone,” because it was the song that first pulled me into this world, and for a much more embarrassing reason than that. At some point, almost involuntarily, I was listening to the Dead to the exclusion of everything else.

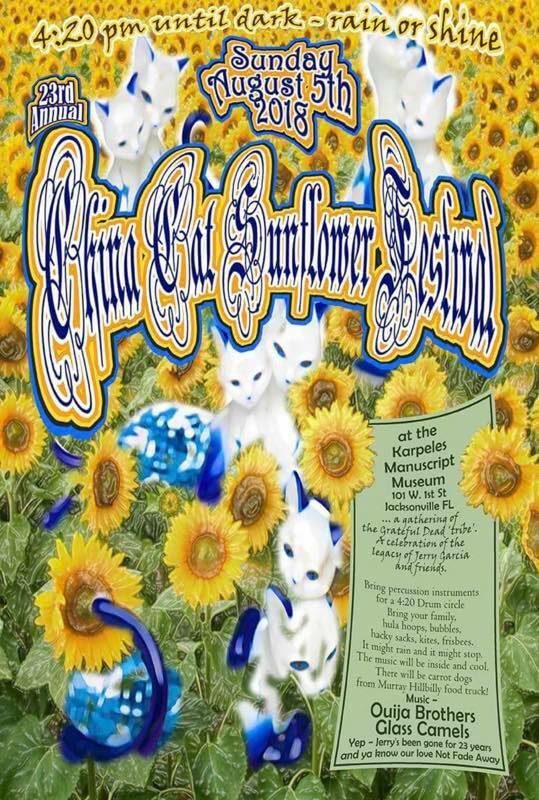

I continued picking up little treasures over the next few months: a recording of the 8/27/72 show, a concert to benefit Ken Kesey’s brother’s struggling yogurt creamery(!) that is legendary amongst fans the 1980 masterpiece “ Althea ,” whose coked-out majesty presented me with an entirely new side of the band. The next song I gravitated toward was “ China Cat Sunflower ,” whose spindly guitar interplay somehow reminded me of the Canadian post-punks Women, a band as chilly and focused as the Dead is loose and exploratory. But he’s gone, Jerry assured me, and nothin’s gonna bring him back. (Part of the reason they sounded so good was that the Dead overdubbed them in the studio after playing the Europe ‘72 tour, I later learned.) Jerry Garcia was singing about some nameless tormentor, the kind of guy who’d steal the face right off your head. Then there were the vocal harmonies, occupying some previously unknown ozone layer between the heavenly cherubs of the Beach Boys and the terminally earthbound growlers of The Band. Phil Lesh got me first, loping from bar to bar like the giant cosmic boot that adorns the Europe ‘72 album cover, under the blissfully misguided impression that the bass guitar is a lead melodic instrument. That was pretty much where things stood between me and the Grateful Dead until early 2016, when someone shared the Europe ‘72 version of “He’s Gone” into one of my social media feeds, and the great shaggy beast looming behind decades of American rock music started to emerge from the mist for me for the first time. The music sounded pleasant but lightweight, and the idea that so many people had built their entire lifestyles around a bunch of geezers singing songs about willow trees and sunshine daydreams was difficult to fathom. I dabbled: I could sing along to “Uncle John’s Band,” owned a dusty copy of Skeletons from the Closet, had spun American Beauty a few times. ” (The Dead indie revival had started in earnest a few years earlier with the “New Weird America” scene, but as a teenager intoxicated by Deftones and Def Jux, I didn’t take notice of those hippies until later.) Like a lot of music nerds my age (27), I started coming around to the idea of the Dead in 2009 or so, when Animal Collective took the press circuit for Merriweather Post Pavillion as an opportunity to sing their praises in seemingly every interview, then sampled them on “ What Would I Want? Sky. Over the last decade or so, the Grateful Dead have been creeping toward respectability, even cult hero status, for art rockers, punks, and indie kids-musicians and music fans who previously might have regarded them as the dorkiest band in America.

And because custie is one of those words used to define an outgroup, like “poser” or “muggle”: If you have to ask the question “what is a custie,” the answer is always “you.” I know I’m a custie, but I’m learning to love the Grateful Dead.

I know I’m a custie, because I happen to pay my dealer exactly $60 for an eighth. Another friend explained: a custie is “a tourist in the world of hippies, as opposed to an authentic head.” A dealer might sell an eighth of weed to a custie for $60, then turn around and sell that same eighth to a real head for $40, the first friend added. I know I’m a custie, because just the other day, a guy I know used the word custie, and I had to ask him what it meant. Let me start by saying that I know I’m a custie.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)